Abstract

This essay presents the methods, as well as the pedagogical effects, findings and results of introducing Ancient Greek in the curriculum of children between three and 12 years old as evidenced over 27 years in the method of Elliniki Agogi. Elliniki Agogi is an award-winning private educational institute established in Greece in the mid-1990s at a time when the teaching of Ancient Greek was questioned and dramatically reduced from the public curriculum. Its aim is to safeguard learning that has its roots in Ancient Greek and to continue to introduce students to the Greek civilisation and its language, using effective, entertaining and artistic methods. This endeavour was based on specific pedagogical models; by learning through experience and through a communication-orientated educational process. With concomitant, cautious organisation and preparation of each lesson a diversified educational curriculum is created that connects the students to their distant past while experiencing positive emotions, filled with ethical paradigms that contribute later to master a fully-shaped personality. 27 years later, studies have come to prove the positive influence of learning Ancient Greek in children’s linguistic and mental abilities. The following study conducted is distinctive in the detailed pedagogical method it provides and validates the importance of teaching the Ancient Greek language to children as early as possible.

Introduction

In Greece, the option of children aged three to 12 learning Ancient Greek as an extracurricular activity was first introduced 27 years ago, when Elliniki Agogi was founded in 1994 by individuals who reckoned that learning Ancient Greek was a determining factor for one’s mental and language development.

The official teaching of Ancient Greek in Greek and most European schools commences in the 7th Grade (at age 13) and according to the Curriculum and the Single Framework Interdisciplinary Education Program, the goals of this module entail that students are to become acquainted with the intellectual output of Ancient Greek, with which modern Greek culture is inextricably linked and which formed the basis for not only the Greco-Roman, but also the Western European culture; another aim is for them to communicate with texts showcasing the importance of the ancient world, which shed light on important moments of ancient cultural activity and provide vital information for the formulation of an approximate, if not accurate per se, image of the ancient world; and lastly, the goal is not only to learn the basic rules and structure of the Ancient Greek language, but to discover and appreciate the literary value of the classics.

n practice, however, the teaching of Ancient Greek in schools is limited in learning the basic rules and structure of Greek through a plethora of texts which, in turn, translates into a tedious instruction of Ancient Greek grammar and syntax, resulting in the students having to passively memorise rules upon rules, emphasising extensive reading (pages and pages) rather than intensive reading (slow, deliberate parsing and translation of a few lines) (see, for example, Lloyd and Hunt, 2021 p. 48). No active involvement is required in the educational process, nor learning through experience. As a result, students often grow apathetic and frustrated with the arduous and pointless efforts they have to make. Eventually, they become repulsed by, and completely disinterested in, Ancient Greek. This is a common feature in many schools where classical languages are taught in the traditional way. The decrease in students who choose to continue classical studies is partly due to the outdated methods which must be drastically changed.

Aiming towards the introduction of the Ancient Greek Language to children in simple and fun ways so that they can comprehend and learn it easily and effortlessly can establish the language’s continuity throughout the years. Moreover, it will equip them with a set of cognitive tools that will eventually allow them to better approach, familiarise with, and end up loving it. The challenges will be faced without fear of the difficulties and a better understanding of the European languages will be achieved. Last but not least, children’s moral development and character building should be some of the additional goals set by schools and institutes, as, multiple models, values, and ideas to be imitated and adopted by, can be found in ancient texts (Kessler, 2000; Montoya, 2020; Rowntree, 1990).

Regarding the instruction of Ancient Greek, emphasis is to be given to the etymology of words, using the ancient Greek philosopher Antisthenes’ method/finding (5th BC) that ‘ἀρχή σοφίας ἡ τῶν ὀνομάτων ἐπίσκεψις’ [‘The basis for wisdom is the etymological examination of words’] emphasising not just the written, but also the spoken, word with the corresponding appropriate communication framework. Ancient Greek is mainly taught in schools to students aged 13 and above as children are deemed to be essentially prepared to better understand Latin and Greek in Middle and High School, where it constitutes part of the official curriculum and is taught systematically. As per van Patten (1993, pp. 435–450), learning Ancient Greek from a younger age clearly involves many cognitive requirements. This finding constituted an additional motive for the constitution of Elliniki Agogi. The institute’s first and foremost goal is that children should grow to love this language; if they love it, they will learn it.

After 27 years of continuous activity and methodical teaching of the Ancient Greek language as an extracurricular activity for just 90 minutes per week, we came to realise that Elliniki Agogi’s methods have altogether shifted the paradigm from its educational purpose throughout the years, to a program that has wide social impact and have led to a gradual change of public opinion regarding the resonance such an activity may have, starting from a young age.

In recent years Elliniki Agogi emerged in Greece as a pioneer in the field, holding classes both physically and virtually. In addition to Ancient Greek classes, the institute’s activities include lectures, visits to museums and sites of archaeological interest, the provision of educational seminars for public school teachers, special educational programs for children in primary education, summer camps, theatrical and musical performances, and also educational and cultural exchange programs in collaboration with schools from other European countries. In 2020, Elliniki Agogi received five awards at the national contest ‘Education Leaders’ Awards’, including ‘Best Educational Center’ and ‘Innovation in Teaching’ 1.

Method of teaching

Elliniki Agogi’s method of teaching of the Ancient Greek language is based on the student-centric model of teaching, by learning through experience and by learning through a communication-oriented educational process. Learning through the arts is a fundamental component of the school’s method that combines learning and understanding the language through singing, acting and drawing.

Τhe epistemological theory which suggests that it is not just knowledge that is of vital importance, but it is also the process through which knowledge is acquired (Groves et al., 2013, pp. 545–556) constitutes a guiding line for the method applied creating favourable learning conditions, allowing students to develop their own mechanisms to absorb and process information and finally to enjoy the class.

Teachers are called on to make this activity as enjoyable as possible by providing creative stimuli. Children are encouraged to participate in storytelling, role-playing, singing, dancing, creative writing and task-based drawing. Art has been proven to help students’ memory and concentration; it encourages focus and listening and develops critical thinking and decision-making skills.

With the appropriate support of their teachers, students are encouraged to speak in Ancient Greek as much as possible, even from the first lesson, taking into consideration that since our students are Greek, the similarities between Ancient and Modern Greek are obvious and extremely helpful.

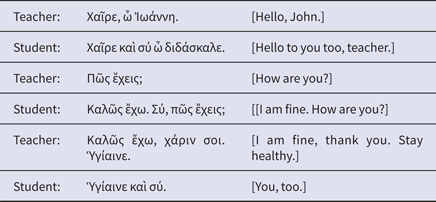

First lesson. Dialogue n.1

This is a short dialogue that goes on in class between teacher and student in the beginning, but continues with students speaking to each other. In modern Greek we say ‘Γεια’ (pronounced yiá) instead of ὑγίαινε, a word short for ὑγίεια. This gives the teachers the opportunity to start speaking of the similarities between the ancient and the modern form of the language. The same goes for the word Χαῖρε which literally means ‘Be happy’ since χαῖρε comes from the word χαρά – happiness, χάριν σοι [thank you] εὐ – χαρι – στῶ in modern Greek, and διδάσκαλε [teacher], δάσκαλε in modern Greek.

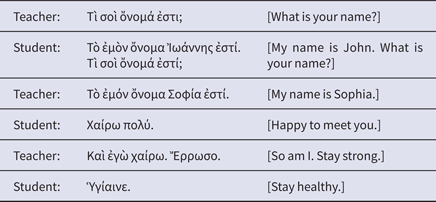

Dialogue n. 2

These are dialogues that the preschoolers learn and repeat relatively easily from the first day. For elementary school students (aged six to nine) the dialogues proceed to where they live: Πού οἰκεῖς; [Where do you live?]. Older students (aged nine-12) are required to copy the dialogues in their note book and continue with other greetings and longer dialogues together with their peers.

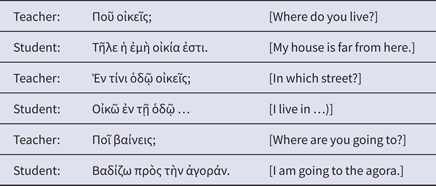

Dialogue n. 3

In this dialogue, the word τῆλε [far] is introduced, which is directly linked to many of the words that we use today, in modern Greek but also, in many European languages: τηλε-σκόπιον/tele-scope, τηλε-όρασις/tele-vision, τηλέ-φωνον/tele-phone, τηλε-μεταφορά/tele-transportation etc. Similar to the word τῆλε, the word οἰκῶ introduces the class to a whole new set of vocabulary based on that small word: οἶκος – (pronounced ecos) [house]), οἰκο–γένεια [family], ἐν-οίκιον [rent], οἰκο-δέσποινα [the lady of the house], οἰκο-δεσπότης [the man of the house] etc., but it is also found in a plethora of European words, for example: οἰκο-λογία/eco–logy, οἰκο-νομία/eco–nomy, οἰκο-σύστημα/eco-system etc.

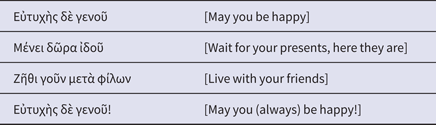

As the school year goes by, the teachers encourage the students to say as many phrases as possible in Ancient Greek, even outside of the classroom, such as: Βούλομαι πιεῖν ὕδωρ [I want to drink water]; Βούλομαι εἰς τὸ βαλανεῖον [I want to go to the bathroom]; Πολλὰς χάριτας [Thank you very much]; Σύγγνωθι μοι [I am sorry]. Figure 1 presents a short list of easy phrases to use in class.

Figure 1. A short list of easy phrases to use in class.

Figure 1. A short list of easy phrases to use in class.

The further the progress and search into the language, the more the children form sentences on their own. One of our most valuable educational tools are Aesop’s Fables. The teachers select short and well-known stories, read them to the students at least twice and then assign roles. Preschoolers pretend to be Aesop’s animal characters and the teacher narrates the story. The students enjoy playing. At school we have plenty of animal dolls, masks and toys to help create a small stage-like place in class and a small group of three to four children dramatise the story. This goes on until all the children participate. Elementary school students are expected to participate in more demanding roles and include the narrator’s/Aesop’s role and write small phrases, whereas older students are asked to write the story in their notebooks and also to discuss the didactic moral, τὸ ἠθικὸν δίδαγμα or epimythion. In ages six-12 all four skills – reading, writing, speaking and listening – are being used and developed. The following example of storytelling is taken from the fable of the fox and the mask (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Story example: Ἀλώπηξ καὶ προσωπεῖον/The fox and the mask.

Figure 2. Story example: Ἀλώπηξ καὶ προσωπεῖον/The fox and the mask.

Preschool students listen to the myth two or three times and draw whatever they think is more impressive. The teacher is very expressive while narrating the myth, using whatever she can find to imitate the fox. She tries to avoid translating and explaining the story to the students. Then they repeat the story phrase by phrase, following the teacher. Then, they engage in role playing while the teacher narrates. One student pretends to be the fox and the other the mask. The ‘fox’ searches the potter’s house, finds the ‘mask’ and starts talking to it by asking questions that are already known, like: Χαῖρε, τὶ σοὶ ὄνομά ἐστι; Τὶς εἶ; Ποῦ οικεῖς; [Hello, what is your name? Who are you? Where do you live?], thus recalling knowledge they have already acquired. Of course, the ‘mask’ never answers, so the ‘fox’ desperately says: Ὦ, οἵα κεφαλὴ! Ἀλλὰ ἐγκέφαλον οὐκ ἔχει. [Oh, such a nice head! It is a pity it has no brains.] Elementary school students additionally do simple etymology exercises – ἐγκέφαλος/ἐν τῇ κεφαλῇ [brains/in the head] – thus learning how to understand seemingly difficult words and try to find derivatives of the word χείρ in modern Greek: χειρ-ουργός [surgeon – chirurgo in Italian], χειρ-ο-κροτῶ [to applaud], χειρ-ο-τεχνία [artifact] etc. Older students finish by also memorising the moral of the story and discuss it further in class. Very often, teachers tend to customise the respective activities based on subject matters that are of interest to the children. Games and children’s songs are translated in Ancient Greek, thus making the lesson fun but also interesting. An example of this is the Birthday song, given below:

Example: The Birthday Song/Τὸ Γενέθλιον ἇσμα.

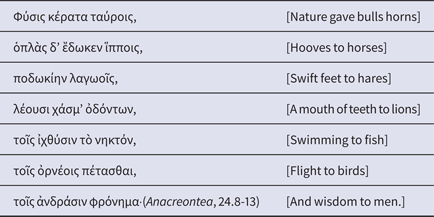

The music is exactly the same as the Happy Birthday song, so the children learn it very fast. The teachers explain the meaning to the younger students and the grammar to the older ones. Another example is the poem by Anacreon ‘Nature’s gifts’ – very simple for children, but also educational in different levels, depending on the children’s ages. This poem is reproduced below. Original music has been composed, and, by singing, students learn the poem very fast 2.

Example: Ἀνακρέοντος «Τὰ δῶρα τῆς Φύσεως»

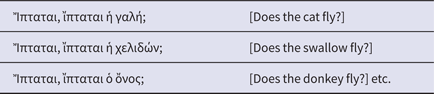

A game that preschoolers love is an old traditional party game called ‘Does the donkey fly?’, which our teachers call «Ἵπταται, ἵπταται.» The children sit in a circle, the teacher points on the floor and wonders aloud whether several animals can fly. If they fly, the children must raise their hands. If not, their hands must remain on the floor3. The words are as follows:

Example

For older students, the enigma of the Sphinx is very popular. Students pretend to be passing by and stop in front of the Sphinx – the role taken by another student. The ‘Sphinx’ then asks: Τί ἐστιν ὅ μίαν ἔχον φωνὴν τετράπουν καὶ δίπουν καὶ τρίπουν γίνεται; [Who has four feet in the morning, two in the afternoon and three in the evening?]. The passers-by reply: Οὐκ οἶδα [I don’t know]. And then the Sphinx pretends to hurt them until Oedipus comes and says the correct answer Ὁ ἀνήρ [A human being].

These communicative games, songs and activities develop communication skills, enhance students’ memory and encourage them to speak and use the words and grammatical forms in other cases. Students aged nine −12 participate in plays where historical events such as the battle of Thermopylae and the naval battle of Salamis are dramatised. It is those same students that started a few years ago with the enigma of the Sphinx and the Fables of Aesop that are now able to read and understand demanding texts from Thucydides and Plutarch 4.

At these ages students learn the use of Ancient Greek in theological texts and prayers that are heard in church such as «Πάτερ ἡμῶν» [‘Our Father’] and «Χριστός ἀνέστη» [‘Christ has risen’].

Lesson planning

Etymological analysis of words

The form in which the vocabulary is organised plays a pivotal role in understanding and producing both the written and the spoken word, as well as retaining information in one’s memory; etymology constitutes an important parameter in teaching the ancient Greek language, as it effectively helps the student understand it better. By teaching words of great productive and compounding strength from which larger word families are formed, children are provided with the ability to expand their intellectual and verbal arsenal and it becomes easier for them to spell words in Modern Greek correctly, as well as read them, since they become familiar with the phonological structure of the spoken word. Etymological analysis contributes to the expansion of cognitive structures and successful incorporation of new information; in each class, children are given a word, and then they are asked to examine its etymology and connect it to its corresponding Modern Greek words so that they can fully understand and interpret it. By doing so, children establish the similarities and differences in the connected words and try to find composites or derivatives. Let’s take for example Aesop’s fable The shipwrecked man and Athena/Ἀνήρ ναυαγός (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Story example: Ἀνήρ ναυαγός/The shipwrecked man and Athena.

Figure 3. Story example: Ἀνήρ ναυαγός/The shipwrecked man and Athena.

In this myth we speak about the word ναῦς [ship] and its composites (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Composites of the word ναῦς [ship].

Figure 4. Composites of the word ναῦς [ship].

Furthermore, we always discuss the last phrase «σὺν Ἀθηνᾷ καὶ χεῖρα κίνει», a phrase that is still widely used in everyday speech in modern Greek, and another opportunity to show the timelessness of the Ancient Greek language.

Image creation and observation

Children either draw a picture or complete an existing one, and this picture functions as the ideal visual-cognitive framework for better understanding, connecting, and representing the concepts that are taken in. Particularly in cases where cognitive requirements are high, this is observed to be the most efficient learning method (Hall, 2009, pp. 179–190; Shulman, 1987, pp. 1–21).

One characteristic example of this is when the following famous quote by Hector in Homer’s Iliad is being taught: ‘Εἲς οἰωνός ἄριστος ἀμύνεσθαι περί πάτρης’ [‘The best omen is fighting for the homeland’] (Iliad 12.243). In Ancient Greek, ‘οἰωνός’ (pronounced ionós) was the bird used by the oracles to foretell the future, and ‘divination’ is as difficult a concept to understand as ‘augury’/‘οἰωνοσκοπία’ (pronounced ionoskopía), which is foretelling the future by observing the flight of birds. So, in this case, students are required to represent augury visually by drawing a picture of the oracle looking to the North (as was the case in the actual practice of augury) and asking for the god’s help. Next, the children are asked to draw a picture of the sun to the right of the oracle, to the East, and at the same time they learn that if the augury bird comes from that direction – from the light – then, it is a good sign, meaning that developments will be positive. The next image they are asked to draw shows the exact opposite, that is, a bird – an ‘οἰωνός’ (pronounced ionós) – coming from the left side of the oracle, the West, where the sun sets and thus represents darkness; therefore, if the augury bird comes from that direction, it is of course a bad sign. Before drawing the final image, teachers ask the children which one do they think is the most likely outcome: in the Iliad, the signs from the Gods are unfavourable, yet Hector ignores them, deciding to fight anyway because he considers the best omen to be fighting for his homeland. By additionally dramatising this scene through dialogue, even more impressive results were recorded, ascertaining once again that it is much easier to memorise what we have understood in depth and, ultimately, what allows us to experience positive emotions. Due to limited time – once a week for 90 minutes – the students’ drawings and crafts are sometimes done at home (for an example, see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Student’s picture of the omen of Hector at Troy.

Figure 5. Student’s picture of the omen of Hector at Troy.

Particular emphasis on studying and rendering images from ancient times is given because, in this way, children become familiar with the aesthetic ideal of ancient Greek art and also indirectly draw information on the cultural and social context in which the Ancient Greek language developed.

Refining speaking skills

Once the main word of the lesson has been analysed and the relevant image drawn, then, students listen to a myth or a story, even a proverb, where they have chosen to frame the said word. Children listen to, comment on, theorise about, and explain the myth, depending on their age. They reach the moral of the story, parallel to incidents and situations from their daily lives, while also making their own judgments. When it comes to teaching Ancient Greek in a classroom, reading Aesop’s Fables and mythological fragments is an ideal choice, as not only do they bring enjoyment and peace to the children, but they also spark their interest and keep their attention, thus successfully contributing to their language skills and mental development. (Bower and Clark, 1969, pp. 181–182).

In other cases, active listening by the students was emphasised through monologues: a basic philosophical quote to the students is presented – always related to the subject of the lesson – and then each one of them is asked to express their opinion on it (in Modern Greek). Every time a student expounded on their opinion – which is in a sense a monologue – the rest of the students must listen carefully and wait for their turn to speak. After each ‘monologue’, the students must pose questions to their classmate regarding the content of their speech. This is considered to be a form of active listening because the students must remain mentally alert in order to properly understand their classmates’ views and pose the right questions afterwards, making equivalent, properly structured comments.

Dramatisation – Theatre

In almost every class, students get to participate in small, improvised theatrical plays which relate to the myth, story or dialogue that they are taught. The students read the simplified version of the story from their books, as written by their teachers. Reading the teachers’ version is always easier than the original text, but also an effective way to prepare students for the original when the time comes. The teacher reads the story, at least twice, using gestures and various pitch, melody, loudness according to the role. This way the children are ‘transported’ to the imaginary setting and become the heroes of the story narrated. Through μίμησις – mimesis, the act of resembling and expressing – students imitate heroes of mythology and history, kings and Byzantine emperors and learn words, phrases and texts more quickly so that they do not forget. Moreover, through acting and role playing, they get acquainted with mythology and major historical events – like the Battle of Thermopylae or the Fall of Constantinople. Later on, when they start reading from the original texts, they realise the abundance of vocabulary and grammatical skills that they have acquired and often wonder where it came from! Soon after they begin classes in Elliniki Agogi, our students’ school teachers report that their daily use of vocabulary expands and their literary expression and overall school performance is improved.

Teaching any language through play is an effective method for children to develop their communication skills and practise the language (Herbert and Pollatos, 2012; Krajewski, 1992). Such educational games allow students to practise various sections of knowledge, such as vocabulary and grammar, mainly as regards to the spoken word, since fluency constitutes a direct goal.

Books – Syllabus

All stories, original or simplified, poems, songs, quotes, tradition, customs, history and all the material used in Elliniki Agogi’s classes are included in five books that we use for students age three to 12: Ἀγωγὴ Νηπίων, Νηπίων Παιχνιδίσματα and Παρὰ Θῖν Ἁλός, written by the philologist Vicky Sakka and Aἰὲν ἀριστεύειν Parts Α and Β, written by the philologist Sophia Goula. The first three books consist of stories and drawing exercises, whereas Books 4 and 5 also includes a few simple grammar exercises after each chapter. No complicated exercises are introduced to the students before seventh grade. Recently we published a book which contains ten of the most popular Aesop’s fables. The texts are in Ancient Greek, Modern Greek and English, but the Ancient Greek text is also written in Latin letters, to encourage non-Greek students to start reading faster. The book also includes a CD where children narrate and act as the heroes of the stories.

Music – Dancing

The use of music in teaching Greek constitutes a pleasant didactic method, since the language itself has musicality, harmony and rhythm.

Καί μέλος ἔχουσιν αἱ λέξεις καί ῥυθμόν καί μεταβολήν, ὤστε ἡ ἀκοή τέρπεται τοῖς μέλεσιν, ἥδεται τοῖς ρυθμοῖς, ἀσπάζεται τάς μεταβολάς.

[Words have melody and rhythm and enjoyable alternations, which please the ear.]

(Dionysius of Halicarnassus)

Having knowledge of the cultural context of music, musicality and its application undoubtedly enriches students’ scope of information. Memorisation of large excerpts from Ancient Greek texts is faster and more effective when rhythmical patterns are used. The language itself has rhythm that is more easily established when combined with rhythmically walking in the classroom or with the use of percussion instruments (drum, tambourine, castanets, sistrum) or by clapping hands. Preschoolers in particular enjoy such activities, as they give them the sense that they participate in a small orchestra.

Beginning with the alphabet, children learn the letters quickly. The tune is joyful and easy to pick up. Combined with rhythmical patterns and gestures, the students easily embody the rhythm and memorise it almost automatically (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Music for learning the alphabet.

Figure 6. Music for learning the alphabet.

Moreover, putting music to verses helps even preschoolers learn long and complex words very fast (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Music for learning a long word (in this case ‘προσετραπόμεσθα’).

Figure 7. Music for learning a long word (in this case ‘προσετραπόμεσθα’).

The aforementioned poem of Anacreon – ‘τὰ δῶρα τῆς φύσεως’ [‘Nature’s gifts’] – is one of our favourites. On this occasion the students are not only expected to sing the words, but also to show what the poem indicates. So, when the poem starts ‘Φύσις κέρατα ταύροις’ [‘Nature gave horns to the bulls’] the children show the ‘horns’ with their hands, on their heads. Since every animal has a ‘gift’ by nature, there is plenty of acting that most children turn into dancing5. This poem is indicative of the Ancient Greek literary discourse and the manner in which it can be rendered in the classroom musically, rhythmically. Therefore, setting any excerpt to music, makes it easier for them to learn and memorise – and much more fun.

Original music is composed for all the poems to ensure that intonation is correct. Choosing pre-composed melodies is not advised; in order to preserve the melody, one may be tempted to change the words, the metre and the punctuation. If any institution wishes to receive Elliniki Agogi’s scores and songs, please feel free to contact our school.

Dancing is also a part of learning the cultural elements of the Greeks, as it had a significant presence in everyday life. Children are shown vase paintings where boys and girls practise dance at school and try to imitate them. At the same time, the teacher presents the similarities of the ancient dances to the modern Greek traditional ones, as for example the dance that Theseus danced in Delos with the 14 boys and girls before going to Crete to kill the Minotaur ‘Γέρανος’ [Géranos – The Crane Dance] which is said to be the equivalent of today’s ‘Tsakonikos’ (Stratou, 1979).

Experiential learning

Learning through experience is a fundamental requirement of education. Students can assume leading roles in the learning process and come into direct contact with the subject through research, observation and specialised activities. In the case of teaching Greek to children, live experience has been deemed to be a useful and functional educational tool.

In Greece we are very privileged since we are able to visit archaeological sites any time of the year we want. The lesson on κάλλος [beauty] and εὐκοσμία [eu-cosmia, good-order] for instance, was done inside the archaeological museum in Athens, during the periodical exhibition ‘Countless Faces of Beauty’ which was about the pursuit and appreciation of beauty. Students not only discussed the concept of beauty and cosmos, but also the world they want to live in. Classes take place while students participate to actual excavations in situ. Additional educational programs include carving of sculptures, preparation of symposia, rowing inside a duplicate of an actual Athenian trireme, the revival of ancient traditions to welcome the new year, such as decorating the ‘iresione’ [‘εἰρεσιώνη’], a branch of olive or laurel wrapped with wool, exchanging ancient Greek wishes and setting New Year carols by Homer to modern tunes6 (Souida Ο 837 [Suidae, 2016], Katsaros, 2002, p. 982).

Celebrating any occasion is also a part of our school’s curriculum. Depicting Dionysian traditions for example and linking them to carnival activities are just some of the activities which take place at Elliniki Agogi for the purpose of the students experiencing the Ancient Greek world. Apart from the educational and entertaining process, it shows to the students that the Ancient Greek culture is not something obsolete that we should forget, but rather a dynamic evolving process that echoes to this day that has fertilised and is alive through languages and cultures in the western world. Greek and Latin are not just languages; by including the communicative approaches, be it through theatre, music, story-telling or animation, it should be made accessible and easy for anyone to learn, as early as possible.

Summer camps are ideal for experiential learning, since teachers spend many hours with students every day and they get to practise everything they learn, through sports, arts, play, speaking, listening and writing. Elliniki Agogi’s summer camp lasts from four to six weeks each year and offers everyday activities from 09:00–14:00.

By exposing students to external stimuli and constantly practising inside and outside the school’s premises, teachers try to activate and identify students’ talents, but also provide access to experiences that reinforce strengths and nurture interests that inspire personal goals for self-actualisation (Jackson, 2011, pp. 91, 95).

The question of complicated grammar and syntax rules may arise to the readers of this article, since those are usually interrelated with the study of classical languages. For more than 20 years and very passionately the last four, we have been trying to personalise learning styles and avoid using traditional course books ‘that can act as monolithic barriers and often demotivate students’ (Schwamm and Vander Veer, 2021, p. 54). It is our vision in Elliniki Agogi to make kids love the Ancient Greek language, by living the experience of understanding in depth the words, the tradition, the culture. In high school most of them will study and learn all the rules that will be given in class and will solve dozens of exercises for each one of them. But by then, they will have accumulated hundreds of words and expanded their vocabulary a great deal to at least understand the text they are reading before trying to grammatically analyse it. Unless they have a positive experience when they are younger, it is very unlikely that they will ever be fond if this fascinating language. Imagine if every school gave its students the opportunity to learn in an easy and fun way through art and mythology, only once a week, Greek and/or Latin; children would be much more prepared to face the challenges of the grammar and syntax which, even though necessary to learn any language correctly, turns the majority of students away, thus preventing them and eventually depriving them of gaining the wealth of knowledge those classical languages offer.

Assessment

In Elliniki Agogi we aim for our kids to enjoy learning. Therefore, there are no grades given or required. Our only requirement is for our students to be present physically or virtually during class. Due to the pandemic, it was impossible for our students to come to class, so we took advantage of our digital platform and connected our students to their classes, so no lesson was missed. This allowed students from all over Greece to connect to our classes and gave us the opportunity to meet extraordinary kids from all over the country, that participated in all of our δρώμενα [events], even from a distance.

We may not grade students; however meetings with parents take place twice a year to maintain contact with the family and inform on the students’ progress. Moreover, a theatrical play at the end of every school year takes place, where all students participate either on stage or virtually – if unable to physically participate. At this play, students present what they have learned during the year. Preschoolers usually present dialogues, poems and songs, elementary school students dramatise Aesop’s fables or other mythological excerpts – like the birth of goddess Athena from Zeus’ head – and our teenagers perform a philosophical play, like Plato’s Crito.

A few months ago, we were informed of the written exams of Classical Greek provided by Language Cert, an internationally recognised company that offers levels A1 and A2 online, for anyone who wishes to assess their level of knowledge in Greek (Poupounaki-Lappa et al., 2021). We found the exams challenging, yet extremely interesting; even though the tests follow communicative principles and are a mixture of authentic and level-adapted materials, at times they draw on classical texts that embody the spirit of Greek writers and their works. We encouraged our students to sit for the Language Cert exams and acquire an internationally recognised Certificate of Knowledge. Most of our students aged 11–16 sat for the exam and succeeded.

Cognitive and mental development

In 2005 Dr. Ioannis Tsegos, Psychiatrist, Group Analyst, President of the OPC (the Institute of Group Analysis, Athens) published his study regarding students in the first three grades of primary school, all of whom attended classes in Elliniki Agogi, verifying the contribution of learning historical spelling and the use of simplified writing (monotonic) on a person’s psycho-educational abilities and functions. All students participating in this study were taught Ancient Greek at Elliniki Agogi for two hours per week and the study found a causal link between learning Ancient Greek and developing one’s psycho-educational skills. The first stage of the study, which was conducted between 1999 and 2002, indicated that learning Ancient Greek spelling had a positive effect on the visual and perceptual skills and functioning of children between the ages of six and nine, as these skills developed rapidly through the learning process. Furthermore, children who were taught the polytonic system (use of multiple accent and breathing marks) showed statistically advanced visual-perceptual and cognitive skills and functioning, which in fact enable better performance at school. According to some specialists, learning Ancient Greek from an early age may help prevent learning difficulties (dyslexia and ‘dyslexias’) and even have a therapeutic effect once such difficulties have manifested (Chanock, 2006, pp. 164–170)

Conclusion

In the future of schooling, what qualifies as ‘official knowledge’ looks old-fashioned in an age where there are many ways to access information and as many ways to attach meaning to that information through learning (City et al., 2012, p. 154) Combining precious yet ‘conservative’ teaching methods with experience, technology and living language methods to the classical languages, seems to be the only way to survive. As with any organisation, schools’ ability to adapt ensures their survival. In Elliniki Agogi, not only do we believe that classical languages need to follow educational reforms, but they should propose new learning techniques, carving the way for others to follow.

Contrary to the general belief that the educational system consists of separate and autonomous entities, where personal development occurs through tedious and demotivating learning styles, Elliniki Agogi’s method of teaching Ancient Greek to children that has been developing, evolving and applied for 27 years and with over 10,000 graduates, proves that by applying means of innovative content-language teaching pursuant to the needs and technology of the modern-day era, Ancient Greek is taught not as an archaic and ‘dead’ language, but rather, as an important part of Greek and other European languages as a whole.

In addition to the aforementioned, teaching Ancient Greek to preschoolers and primary education students, apart from an educational standpoint, also has significant effects on the individual’s cognitive and linguistic levels; the global human values obtained from studying Ancient Greek texts, values which laid the foundation for Western culture and led humankind to great intellectual progress, are now adopted by children, who develop morally, emotionally and mentally by being exposed to them. Learning Ancient Greek at an early age gives the opportunity to children to develop a strong personality and to understand the important role they play within society, which in turn, will result in setting and planning for a better future for generations to come.

Footnotes

1 See Education Leaders Awards 2020: https://www.educationleadersawards.gr/_pdf/education_leaders_awards_2020.pdf.

2 For a performance of Anacreon’s song, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0MhNID3zEVs (accessed 23 April 2022).

3 For a performance, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dGRG7IiM_5w (accessed 23 April 2022).

4 For a performance of the ‘Battle of Thermopylae’, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4x_WCZbARQA (accessed 23 April 2022); and of the ‘Battle of Salamis’, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6cdG2RtJ7UQ (accessed 23 April 2022). With English subtitles: Thermopylae: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uVCupHaKwYA (accessed 7 May 2022); and Salamis: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qF_8poYTiUY (accessed 7 May 2022).

5 See https://youtu.be/0MhNID3zEVs (accessed 7 May 2022).

6 For a visual presentation during Covid-19 virtual classroom era (Greek audio with English and Greek subtitles), see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOGO2TLko_g (accessed 23 April 2022).

References

Bower, GH and Clark, MC (1969) Narrative stories as mediators for serial learning. Psychonomic Science 14, 181–182.Google Scholar

Chanock, K (2006) Help for a dyslexic learner from an unlikely source: the study of Ancient Greek. Literacy 40, 164–170.Google Scholar

City, EA, Elmore, RF and Lynch, D (2012) The Futures of School Reform. In Mehta, J, Schwartz, RB and Hess, FM (eds), Redefining Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, p. 154. Google Scholar

Groves, M, Leflay, K, Smith, J, Bowd, B and Barber, A (2013) Encouraging the development of higher-level study skills using an experiential learning framework. Teaching in Higher Education 18, 545–556.CrossRef Google Scholar

Hall, E (2009) Mixed messages: the role and value of drawing in early education. International Journal of Early Years Education 17, 179–190.CrossRef Google Scholar

Herbert, BM and Pollatos, O (2012) The body in the mind: on the relationship between interception and embodiment. Topics in Cognitive Science 4, 692–704. Google Scholar

Jackson, Y (2011) The pedagogy of confidence. In The Practices. New York, NY: Teachers’ College, Columbia University, pp. 91, 95.Google Scholar PubMed

Katsaros, V (2002) Souida Byzantine Dictionary, Vol. 837. Thessaloniki: Thyrathen Publications, p. 982 (in Greek).Google Scholar

Kessler, R (2000) The Soul of Education: Helping Students to Find Connection, Compassion, and Character at School. Alexandria, VA: Association for Superv sion and Curriculum Development.Google Scholar

Krajewski, H (1992) The Drama Process: Language Development through Movement (Unpublished Masters Thesis). Brock University, St. Catharine’s, Ontario.Google Scholar

Lloyd, M and Hunt, S (eds) (2021) Communicative Approaches for Ancient Languages. London: Bloomsbury Academic.Google Scholar

Montoya, AOD (2020) Practice and theory in the moral development: question of awareness. Educational Journal 9, 1–8.Google Scholar

Poupounaki-Lappa, P, Peristeri, G and Coniam, D (2021) Towards a communicative test of reading and language use for Classical Greek. The Journal of Classics Teaching 22, 98–105.Google Scholar

Rowntree, D (1990) Teaching through Self-Instruction: How to Develop Open Learning Materials. London: Kogan Page.Google Scholar

Schwamm, JM and Vander Veer, NA (2021) From reading to world building, collaborative content creation and classical language – learning. In Lloyd, M and Hunt, S (eds), Communicative Approaches for Ancient Languages. London: Bloomsbury Academic.Google Scholar

Shulman, LS (1987) Knowledge and teaching: foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review 57, 1–23.Google Scholar

Souida (2016) ‘Ὅμηρος’. Suidae Lexicon, 3rd Edn. Thessaloniki: Thyrathen Publications.Google Scholar

Stratou, D (1979) Greek Traditional Dances. Athens: Greek Educational Books Organisation (in Greek).Google Scholar

van Patten, B (1993) Grammar-teaching for the acquisition rich classroom. Foreign Language Annals 26, 435–450.Google Scholar